In Suspiria (1977), Jessica Harper wonders, Is that peacock thing beautiful or just tacky?

Early on, I woke up and wandered out of my bedroom to find someone watching the late show. A wealthy family kept one of their brothers or uncles locked up in a room in the tower. He had escaped somehow and came lumbering down the staircase, terrifying the servants, until one of the family intervened and convinced the uncle/brother to return to his hidden chamber. The man or monster was never seen; the camera looked out from his eyes—a fish-eye lens like the peephole in our front door. We were inside the unfortunate relative during his brief moment of freedom. For years afterwards, I was secretly convinced that I had a brother living in a hidden room under the garage, accessed through the back of a wardrobe closet in the downstairs furnace room. I never told my family that I knew about my monstrous brother, or made the connection with this early horror movie experience, until long after I was an adult. Ah, the power of cinema.

Later, I seriously considered skipping trick-or-treat one year so as not to miss the premiere of Devil Dog, Hound of Hell. Luckily, I came to my senses. Free candy versus what would undoubtedly turn out to be a pathetically bad TV movie. Still: Devil Dog, Hound of Hell. The title itself is as tasty as a Tootsie Roll.

All those made-for-TV movies. Why were they all 90 minutes and not 2 hours back then? How was this decision made? And why did the running times change? Perhaps it was the fault of those gargantuan miniseries. Winds of War, anyone? In any case, in addition to Get Christie Love and Stockard Channing in The Girl Most Likely To…, there were some works of terror that seemed very thrilling at the time. Duel from Steven Spielberg. And Gargoyles, which burrowed deep into my imagination. It opens with a researcher visiting a roadside attraction/curio shop in the Desert Southwest and discovering a strange, horned, humanoid skeleton in the back room. I had visited so many of these creepy shacks off the highway during family camper trips through Arizona and New Mexico, that the scenario seemed eminently plausible. When the researcher flees the burning shack after the death of the crusty old man who possessed the skeleton, he takes the horned skull back to his motel room. Surely, he could have foreseen this was a bad idea! The movie was exactly scary enough for a seven-year-old.

The Gold Standard of 90-minute TV horror movies of the 1970s must be Trilogy of Terror. The first two parts are difficult to recall in any detail, but the last one…the talk of the playground. Karen Black, giving a tour-de-force performance, plays a woman who has somehow trapped herself in her own apartment with a fetish doll possessed by a demonic spirit. Among the lessons learned: Do not try to grab a knife by the pointy end.

By the time my pubescent years rolled around, I was creating monsters and mise-en-scene for other trick-or-treaters in my parents’ front yard (Those plastic eggs full of green slime? Essential), and I had entered my Junior Cinephile Period. More precisely, I was cultivating my Bad Cinema Fascination (and I still love them, bad movies, although my standards are higher [lower?] than they used to be when I would watch anything in search of those jewels of awful greatness). Plan 9 From Outer Space is pretty much the epitome of this…um…genre? And Criswell’s introduction can serve as the keynote address. So sublimely ludicrous, this speech could have been on the bill for Dada Night at the Cabaret Voltaire.

And then I hunted down VHS treasures like Exorcist II: The Heretic. It seems to be hard to locate in our current moment, but this film is ripe for rediscovery. Director John Boorman after Zardoz and before Excalibur. Richard Burton in his long, bellowing decline. James Earl Jones in a grasshopper costume. About as tangential to the original as a sequel could be and still get funding from a major studio. Equal parts tedious and marvelously weird. The climax features a plague of locusts and Linda Blair tap-dancing. The trailer works beautifully as a disco-goth music video.

Then there was Invader from Mars, the 1953 version that I had to track down after seeing publicity stills in Starlog Magazine. I thought it was going to be a so-bad-it’s-good, but it is actually pretty much just good. The alarming tale of little boy who finds first his parents and then his entire world taken over by mind-controlling aliens who have hidden themselves under the sandpit at the back of the yard. The film is understood as an hysterically anti-communist Red Scare allegory, but it resonated with me as a gay adolescent: your parents, your teachers, the whole town are your enemies. They are conformist zombies, and you are fundamentally different from them. You cannot trust them, and you need to escape!

And now, some musical treats.

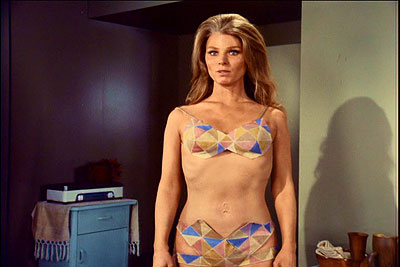

The obvious choice here is The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The film escapes the crushing respectability of being a truly good movie by peaking way too early. We are given “Damnit Janet,” “The Time Warp,” and then this number in quick succession. Then the narrative meanders aimlessly, possibly redeemed by the remarkably louche and languid ending where everyone is in fishnets prancing around the pool. If Anne Hathaway can snag an Oscar for her enlivening five minutes jolted into the corpse of Les Miserables, then Tim Curry was surely robbed. (And if you watch it below, you can practice your Italian!)

One of the concoctions Joseph Losey came up with in his expatriated career phase was a seaside English tale featuring an age-inappropriate romance, expressionist sculpture, and radioactive children. And Oliver Reed leading a gang of what I suppose are Teddies, somewhere between Clockwork Orange and We’re the Boys in the Chorus, We Hope You Like Our Show. The title is great: These Are The Damned (I want to write that book!). The film opens, after some moody credits, with a sorta musical number, a perfect tune if you are a Kenneth Anger fetishist. There are subtitles here, so karaoke everybody!

Although not strictly a musical number, the first killing from Dario Argento’s Suspiria serves to illuminate the cinematic parallels between elaborately choreographed slapstick, Hollywood production numbers, and gorefest death scenes. Hyperviolent but detached and process-oriented, it could almost be Matthew Barney performance art, or kinetic sculpture (and possibly aesthetically misogynist: pretty girls make the best corpses). What makes the scene thrilling is the set and lighting design (such colors! those wall treatments!) and Goblin’s rarely equalled soundtrack.

David Lynch is the master of the unlikely musical interlude (though sadly not in Dune, which would have been fun). This scene from Blue Velvet is more potent in context, but standing alone, it still underlines the service Lynch performed by reminding us how amazing Roy Orbison is. Happy Halloween In Your Dreams!

Have a safe holiday! (Suspiria 1977)