[A version of this essay was presented at a Pacific Ancient and Modern Languages Association (PAMLA) conference panel on Nostalgia.]

Nostalgia for Neverlands:

Cult Films, Camp, and Cobra Woman

#1 — Welcome to the first station of our pilgrimage to Cobra Island. Please gather around, and I will reveal to you The Story Thus Far:

Somewhere in the South Pacific, on some island, at some time in the colonial past, Ramu and Tollea are about to be married. The groom, Ramu, is so excited about his imminent vows that he has forgotten to put on his shoes. Despite his exotic name, Ramu, is a solid all-American fellow, and Tollea is…well, just before the ceremony, Tollea has been kidnapped! She has been abducted back to her homeland, Cobra Island. And so Ramu climbs into his little sailboat vowing to get her back. There is a stowaway on board: Kado, a young man who prefers to dress in a pair of tight white shorts and nothing else. Kado is Ramu’s…um…companion. Or ward. Or something like that. When these two reach Cobra Island, many adventures ensue.

It turns out that Tollea has a twin sister, Naja, who has happily been lording it over the commoners as the high priestess of the Cult of the Cobra. Naja is none-to-happy that her sister has been returned to the island to threaten her claim to dynastic succession. The island is not big enough for more than one sister to interact with the snake god and manage sacrifices to the ever-smouldering volcano. Something’s got to give!

Oh, and there’s also a mischievous girl chimpanzee, named Coco.

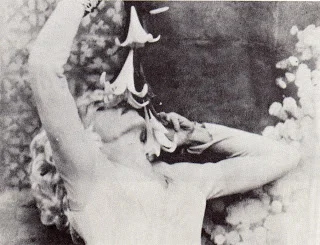

#2 — Now if you’ll step over here and peer down through this opening in the rock, you will be able to witness the island’s most sacred Cobra Ritual already in progress. That’s Naja down there dancing in case you were wondering:

Cobra Woman

Watch the Coming Attraction!!!

#3 — We’ll pause a moment here to examine the informational plaque:

The source of all our knowledge of Cobra Island is the 1944 film Cobra Woman. The film was a Universal Studios production, one of a series of World War II-era films pairing actor John Hall and the Dominican Republic-born actress who came to be known as the “Queen of Technicolor,” Maria Montez. Cobra Woman and its companion films like Ali Baba and White Savage are works of escapist exotica offering wartime viewers a diversion into jungle or desert locales, with romance and dangerous intrigue, often—as in Cobra Woman—featuring Sabu, the young actor who had become the living embodiment of colonial fantasy, and all of it offered up with a moderately-priced amount of spectacle staged on the studio backlot. Whenever you see one of those movies that take place at a movie studio, and the commisary is full of women in evening gowns and turbans, and the men in the background all carry spears while stagehands wheel cages of wild animals across the road, the movie they are making on the soundstage next door is Cobra Woman. The film was directed by Robert Siodmak, who is best known for thrillers like The Spiral Staircase, and his excellent contributions to the film noir genre like Criss Cross and the The File on Thelma Jordan. It’s safe to say that no one has ever made the case for Siodmak’s status as a film auteur based on his work on Cobra Woman.

Nonetheless, the film was extremely popular in its own time. These films were Universal’s biggest money-makers, and they later filled the schedules of the early television era. Then they and their star, Maria Montez, were largely forgotten. Dismissed, derided, and abandoned, except by a small coterie of mostly gay male fans. Foremost among these devotees was the photographer, filmmaker, performance artist, bohemian New Yorker, and Andy Warhol rival, Jack Smith.

#4 — You may have seen his name on the broadsheets pasted around Cobra Island’s docks or on one of the pamphlets dropped from a passing hot air balloon. Jack Smith’s manifesto “The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez” was first published in the Winter 1962 issue of the influential journal Film Culture. In this essay, he attempts the reinvigoration of Maria Montez as a cinema idol, but not with a conventional strategy that might point to her films as underrated gems or her acting gigs as overlooked great performances. Instead, Jack Smith attacks the traditional critical standards themselves. He argues that those looking for good performances in the films of Maria Montez are missing the point: “You can have GOOD PERFS & no real belief. GOOD PERFS that give you no magic – oh I guess a sort of magic, a magic of sustained efficient operation (like the wonder that the car motor held out so well after a long trip).” [“Appositeness,” p. 25] He defends Montez by asking, “Why insist upon her being an actress – why limit her? Don’t slander her beautiful womanliness that took joy in her beauty and all beauty – or whatever in her turned plaster cornball sets to beauty. Her eyes saw not just beauty but incredible, delirious, drug-like hallucinatory beauty.” [“Appositeness,” p. 25] In support of the conclusions of Smith’s weird, earnest, hectoring, sloppily exuberant celebration of Montez, I would point you to the smile we saw on Ms. Montez’s face at the end of the cobra ritual. Whether or not this grin makes any sense for this character or the dramatic situation, her sense of delight and triumph at the spectacle surrounding her is palpable. Condemning maidens to death in a volcano has never seemed so exhilirating.

#5 — Our pilgrimage now compels us to trek for a moment into the nearby Grotto of the Critics. You may recognize many of the shrines, totems, and reliquaries located here. The buzzing Xerox machine of “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” the dark and treacherous cavern of Gender Trouble, and somewhere the distant sound of subalterns speaking (if they can, that is). All pilgrims to Cobra Island must pause to touch foreheads to the icon of Susan Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp’” of 1964. As Sontag herself explains at the outset, “Many things in the world have not been named; and many things, even if they have been named, have never been described.” [“Notes,” p. 275] Yet, if the concept of camp was once underdefined, Sontag’s endlessly-cited essay has now ensured that “camp” as an intellectual category has become overdetermined. The essay has been so persuasive in delineating the territory of camp and so successful in diagramming the operations of the camp sensibility, that its conceptual framework of provisional numbered “notes,” now seem the bulleted stipulations in a piece of legislation or a Biblical exegesis.

Many of Sontag’s central contentions have become accepted as givens: for example, her assertion that the camp sensibility celebrates the unintentional inadequacy of artistic ambition—in her words, “a seriousness that fails” [“Notes,” p. 283], or her division of Camp into the “naïve,” unintentional variety and the inferior, deliberately winking kind [p. 282].

The deficiency of “Notes on “Camp’” may stem from the essay’s seemingly resolute disinterest in considering the reasons a camp sensibility develops and persists. Sontag is careful to illuminate the mechanism and products of Camp, but she is reticent to examine the key adopters of this sensibility and their motivations for embracing Camp as a viewpoint. In this regard, it is likely revealing that Sontag leaves her mention of “homosexuality” until Note Number 51 (out of 58). Sontag suffers no illusions about the primary practitioners of Camp, but she goes to great lengths to profess that Camp is “much more than homosexual taste” [“Notes,” p. 290]. She takes even greater pains to separate herself from the Campers when she informs readers, “I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it. That is why I want to talk about it, and why I can. For no one who wholeheartedly shares in a given sensibility can analyze it; he can only, whatever his intention, exhibit it. To name a sensibility, to draw its contours and to recount its history, requires a deep sympathy modified by revulsion” [“Notes,” p. 276]. Given what we now know about Sontag’s lifelong struggle to accept and express her own same-sex attractions, it is tempting to earmark this passage as evidence of an author protesting too much, but a more immediate explanation for her inclusion of this passage is that her venue for the essay was the Partisan Review, one of the key publishing organs of the New York Intellectuals. For this audience, Sontag positions herself as an anthropologist, coming back from a distant island with her observations of a strange people and their curious rites and customs. Such was the repressive culture of the time that everyone accepted and expected the maintenance of a level of plausible deniability in public discourse around queerness of many sorts. Sontag’s professed “revulsion” reads as a genuflection to cultural norms. Curiously, her admiring essay from the same year on Jack Smith’s film work avoids this nose-pinching and spreads just a slight mist of disinfecting distance.

#6 — You will notice, as we depart the Sontag niche, that Jack Smith’s own efforts have not been enshrined in the Grotto. Unlike Sontag, who departed Cobra Island with her neatly typed notes and ambitions as a public intellectual, Smith was never interested in critical analysis per se. His writing stands athwart of the recognition of movies as artifacts worthy of academic pursuit, a codification of film studies that was underway during the most productive years of his artistic life. Smith had no patience with critics; he disdained the “enveloping cloud of critical happiness” [“Appositeness,” p. 28], which made it acceptable to love movies, but only through an intellectual aperture, preferably one focussed on the latest serious European art cinema. By contrast, his own essays, while they have been influential, are more poetry than theorization. And his most significant meditations on the power and beauty of Cobra Island have come in his photographs, films, and performances. What he wanted to highlight and celebrate were those films he calls “secret flix,” movies with a value and interest that lay not in the film itself, but in its significance to its audience—and not “audience” as a public mass but “audience” as a single spectator enchanted by the image on the screen. A love of these secret flix might be embarrassing—Smith felt that he had to “sneak away to see M.M. flix” [“Appositeness,” p. 30]—but it was essential, it was necessary for survival.

#7 — As we enter the tunnel that will convey us to the heliport and the end of our sojourn on Cobra Island, I recommend that you look back over your shoulder at the land we are departing: dense jungle, wide-mouthed garish flowers, a crumbling temple partially obscured, all framed by the tunnel’s darkness. Will we miss it, this landscape already receding from view? Will we remember it with fondness and longing? If nostalgia is homesickness, can we become nostalgic for a place where we have never been except in our dreams? A place that never has been and never will be?

In Mary Jordan’s 2006 documentary, Jack Smith and The Destruction of Atlantis, several collaborators and friends of Jack Smith attempt to explain the hold that Maria Montez and her filmography had over his imagination. Most of them mention childhood and the early, formative discovery of Ms. Montez at the moviehouse or on television. The playwright Ronald Tavel tries to explain her power: “She’s bringing this fantasy world…breathing life into it and making it a place for you to live. YOU the oppressed, and did you evah feel oppressed as a six year old gay boy. Did you evah!”

As Tavel’s observation suggests, the concept of childhood under review in Smith’s life is not some “golden age” of innocence and bliss. For a gay child—especially one growing up in intensely conformist and homophobic mid-twentieth century America—a sense of alienation and rejection could easily overwhelm any rosy memories of birthday parties, softball games, and cabins by the lake. In Mary Jordan’s documentary, Jack Smith’s sister recalls that he was “a very unhappy little boy,” and the film offers a letter from Smith to his mother that overflows with resentment: “Dear Mother, I try to remember something to love you for but the more I remember the more bitter I feel because all I can remember is neglect, bitter fights, punisments [sic], vindictiveness, petty retaliations, and stupid mishandling of my childhood.” He blames his mother for his nervousness, his impotence, and his homosexuality, and whether or not his scorn is fully justified, it supports author Gary Indiana’s contention that “a person like Jack probably comes from somewhere they want to get away from and forget about” [Atlantis]. If the roots of camp affection—for Maria Montez or any diva or dreamworld—grow from the soil of childhood, that nostalgia may arise in spite of, not because of, the childhood involved.

Nostalgia may also be understood as a longing for homeland, and even if this craving cannot be satiated by any conceivable turn of events, there is usually some historical validity, some kernal of verifiable memory, that sustains such longing. While the reinstatement of Imperial Russia or the Muslim Caliphate may not be forthcoming, quantifiable shreds of past reality provide the nutrients for nostalgia. By contrast, Cobra Island has no claim to any geographical or historical existence, yet it continued to keep its hold on Jack Smith’s imagination.

If a group of gay people can be conceived of as a community, with a unique sensibility, a culture, does it follow that these gay people would long for repatriation? And if so, where is their home country to be found? In some as-yet-undefined utopian future? Or lodged in some tantalizing—if nonexistent—past? If the act of nostalgia is a conservative operation—the glow is always from behind us in the tunnel—perhaps camp has a conservative function as well: looking back, enjoying the past not for what it actually was, but for what it wished it could have been.

Escapism has been made synonymous with self-indulgence, with the masturbatory, with triviality. But perhaps Jack Smith’s veneration of Maria Montez reveals that escapism is not empty entertainment, that camp is not merely a refusal to take anything seriously, that an escape into fantasy can be an act of self-preservation, even a brave one. Such a fantasy can shelter the child, and then it can become the imago of childhood that the adult recalls with fondness.

#8 — On board the helicopter, you may wish to glance out the starboard windows as we ascend, to catch a glimpse of Cobra Island from above. In the air, the island looks like a map drawn in crayons. A stage set with the palm trees in pots and raw two-by-fours propping up the temple walls. A rooftop in 1960s New York scattered with fabric and debris:

Flaming Creatures

“Flaming Creatures” from 1962 was the last film that Jack Smith completed. He continued shooting film through the 60s and beyond, and he offered exhibitions of works-in-progress like “Normal Love,” shot in 1964-65, but he never brought another work to a definitive conclusion, as if he never wanted any of his projects to become fixed in form, as if he never wanted them to end, as if he never wanted to lose the feeling the act of creation gave him.

“Flaming Creatures” was shot on the rooftop of a theatre in Manhattan with men and women of various genders in various states of dress and undress, lounging and posing, while a soundtrack lifted from old Maria Montez movies and radio pop songs crackles through the speakers. The film stock is black and white and grainy. And so over-exposed that every shot threatens to dissolve into white. The very air is a dairy product: the milk of memory, the milk of amnesia. Perhaps it’s an amniotic fluid, and the whole film is a disturbance in the womb. There is a lot of vamping, and some actual vampires. The film is suffused with sexuality—and, for that reason, screenings of the film were banned in 22 states and 4 countries for most of the decade after it was made—but its images could be the erotic impressions of a child. The waggling of bared breasts. The wiggling of limp penises. When characters do come together with passion, the result looks more like violence than arousal. There is a rape and then an earthquake. Perhaps this is how sex might look if you observed it or imagined it before you knew what sex was for.

Jack Smith shoots much of the action from overhead. In Midnight Movies, J Hoberman writes that Smith rigged up some contraption allowing him and his camera to swing over the actors as they writhed on the rooftop below, and from time to time he would rain chunks of plaster down onto the scene [Midnight Movies, p. 50]. The view is less like the Gods on Olympus peering down at mortal folly than a child staring down intently at his playthings. Creating a delirious beauty with a handful of unlikely toys requires real concentration. It’s a serious game.

Normal Love - Jack Smith