In a demonstration of the internet’s ability to aid and abet the impulses of a wandering mind, I took a break from a project yesterday to read an article about Neandertals and ended up, many minutes later, contemplating the interior of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

All discussions of Neandertals seem to veer into examinations of their skulls. I was familiar with their bulgy foreheads, of course, from their appearance in countless cartoons, but the intriguing feature I had never paid any attention before is around the back: the occipital “chignon” (shown in this image as the less chic, down-market “bun”):

chignon or sans chignon?

Judging from the online image banks, Neandertals have gotten a lot softer and cuter since I studied their pictures in various encyclopedias as a child. They have exchanged their dark, hairy, glowering sexiness for a more ethereal, wistful, even wounded look. Their children clearly made necklaces of flowers and played with elves, and I feel bad if we Homo sapiens were responsible for their extinction:

From the Neandertal chignon, it was a quick sidestep through a personal health question (because the internet is so helpful in calming our medical fears)--Does the bump on the back of my own head mean I am a Neandertal descendent?—then on to the eye-opening topic of head binding. More of this sort of thing has gone on than I realized. There are some beautiful and eerie photographs of members of the Mangbetu people of northeastern Congo exhibiting this feature. Many of these photos seem to come from the same time period and photographer, but the sites I looked at did not attribute them to anybody, and further, it is the lazy protocol of the internet browse that I can’t be bothered to do the research either:

After this, I took a jump to a 2005 reconstruction of Tutankhamun’s appearance, which has lead some to speculate about head binding among the Ancient Egyptians:

I am interested in the decision to decorate this effigy with eyeliner. Is it true that no pharaoh would be seen without it?

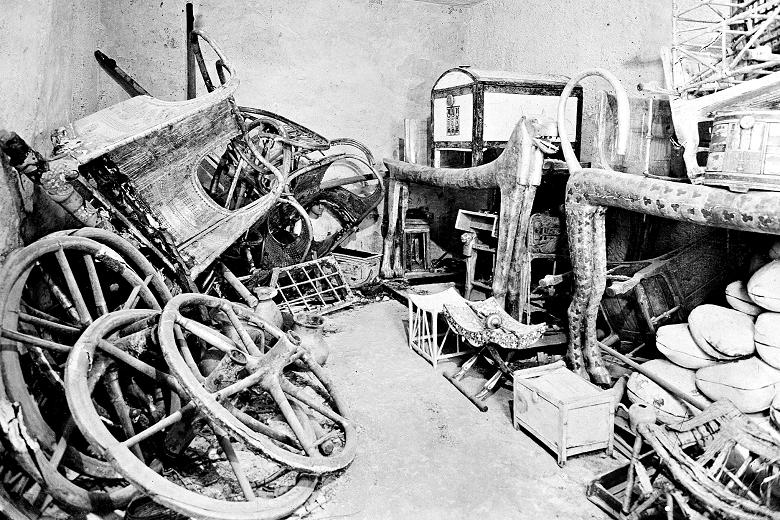

From there, it is on to the phantasmagoria of Tut imagery. By far the most evocative for me are the photographs that Harry Burton took during Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon’s initial explorations of the tomb and its contents in 1922. The 1920s depicted here seems as lost to time as Imperial Egypt, and the entry into the tomb feels like it should be pictured, at best, by a cheaply-printed Victorian etching. Yet here are the photographs, in the stark black and white of a Weegee crime scene or Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, including some haunting ones I had never seen before like the shot of the linen shroud and floral necklaces inside the sarcophagus:

One of my favorite ways to wander online is through the Google Image function. I would not suggest this approach if you are attempting actual research (or teaching someone how to use the internet), but, with its radical separation of image from context, these searches become a marvelous Cognitive Dissonance Engine. The Surrealists would have loved this. For example, next to a publicity shot of Tony Curtis, this image of the antechamber of Tutankahmun’s tomb—the first sight that greeted Howard Carter by candlelight through a gap in the wall—can be clicked on to reveal the following tagline:

"Its stylized cursive neon sign was designed by Betty Willis, creator of the iconic “Welcome to Las Vegas” sign. The exterior walls had murals of dancing couples and hot cars, the interior…"

What I like about this image is that it reminds me of somebody’s grandmother’s garage. Of our own, in fact. Granted, Tutankhamun had nice things in his garage: gold, lapis lazuli, canopic jars of translucent alabaster. Ours is pretty much stuffed with cardboard.